Belgium

Kingdom of Belgium | |

|---|---|

| Motto: Eendracht maakt macht (Dutch) L'union fait la force (French) Einigkeit macht stark (German) (English: "Unity makes strength") | |

| Anthem: La Brabançonne Dutch version: French version: | |

Location of Belgium (dark green) – in Europe (light green & dark grey) | |

| Capital | City of Brussels 50°51′N 4°21′E / 50.850°N 4.350°E |

| Largest city | Brussels-Capital Region |

| Official languages | |

| Ethnic groups (2024)[1] | |

| Religion (2021[2]) |

|

| Demonym(s) | |

| Government | Federal parliamentary constitutional monarchy[3] |

• Monarch | Philippe |

| Alexander De Croo | |

| Legislature | Federal Parliament |

| Senate | |

| Chamber of Representatives | |

| Establishment | |

| 1789–1790 | |

| 1790 | |

| 1814–1815 | |

| 1815–1839 | |

| 25 August 1830 | |

• Declared | 4 October 1830 |

| 19 April 1839 | |

| 1970 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 30,689[4] km2 (11,849 sq mi) (136th) |

• Water (%) | 0.64 (2022)[5][6] |

| Population | |

• 2024 census | |

• Density | 383/km2 (992.0/sq mi) (22nd) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2022) | low inequality |

| HDI (2022) | very high (12th) |

| Currency | Euro (€) (EUR) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

• Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Drives on | Right |

| Calling code | +32 |

| ISO 3166 code | BE |

| Internet TLD | .be and .eu |

| |

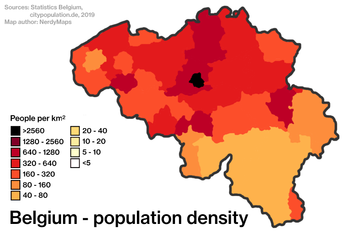

Belgium,[a] officially the Kingdom of Belgium,[b] is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to the south, and the North Sea to the west. It covers an area of 30,689 km2 (11,849 sq mi)[4] and has a population of more than 11.7 million.[7] With 383/km2 (990/sq mi), Belgium's population density ranks 22nd in the world and 6th in Europe. Belgium is part of an area known as the Low Countries, historically a somewhat larger region than the Benelux group of states, as it also included parts of northern France. The capital and largest metropolitan region is Brussels;[c] other major cities are Antwerp, Ghent, Charleroi, Liège, Bruges, Namur, and Leuven.

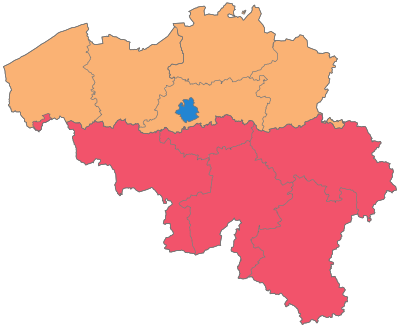

Belgium is a sovereign state and a federal constitutional monarchy with a parliamentary system. Its institutional organization is complex and is structured on both regional and linguistic grounds. It is divided into three highly autonomous regions:[13] the Flemish Region (Flanders) in the north, the Walloon Region (Wallonia) in the south, and the Brussels-Capital Region in the middle.[14] Brussels is the smallest region but also the most densely populated and the richest by GDP per capita. Belgium is also home to two main linguistic communities: the Flemish Community (Dutch-speaking), which constitutes about 60 percent of the population, and the French Community (French-speaking),[d] which constitutes about 40 percent of the population. A small German-speaking Community, making up around one percent of the population, exists in the East Cantons. The Brussels-Capital Region is officially bilingual in French and Dutch,[16] although French is the majority language and lingua franca.[17] Belgium's linguistic diversity and related political conflicts are reflected in its complex system of governance, made up of six different governments.

In 55 BC the region around Belgium was dominated by the Belgae, and became part of the Roman Empire. In the Middle Ages, the region was part of the Carolingian Empire, and much of it was later part of the Holy Roman Empire, and subsequently the Burgundian Netherlands. Belgium's central location has kept it relatively prosperous and connected both commercially and politically to its bigger neighbours. The country as it exists today was established following the 1830 Belgian Revolution, when it seceded from the United Kingdom of the Netherlands, which had incorporated the Southern Netherlands (which comprised most of modern-day Belgium) after the Congress of Vienna in 1815. Belgium has been called "the Battlefield of Europe",[18] a reputation reinforced in the 20th century by both world wars.

Belgium was an early participant in the Industrial Revolution,[19][20] and during the course of the 20th century, possessed a number of colonies, notably the Belgian Congo and Ruanda-Urundi.[21][e] These colonies gained independence between 1960 and 1962.[23] The second half of the 20th century was marked by rising tensions between the Dutch-speakers and French-speakers, fueled by differences in political culture and the unequal economic development of Flanders and Wallonia. This continuing antagonism has led to several far-reaching state reforms, resulting in the transition from a unitary to a federal arrangement between 1970 and 1993. Despite the reforms, tensions have persisted: there is particularly significant separatist sentiment among the Flemish; language laws such as the municipalities with language facilities have been the source of much controversy;[24] and the government formation period following the 2010 federal election set a world record at 589 days.[25] Unemployment in Wallonia is more than double that of Flanders, which boomed after the Second World War.[26][27]

Belgium is a developed country, with an advanced high-income economy. The country is one of the six founding members of the European Union, and its capital, Brussels, is the de facto capital of the European Union itself, hosting the official seats of the European Commission, the Council of the European Union, and the European Council, as well as one of two seats of the European Parliament (the other being Strasbourg). Belgium is also a founding member of the Eurozone, NATO, OECD, and WTO, and a part of the trilateral Benelux Union and the Schengen Area. Brussels also hosts the headquarters of many major international organizations, such as NATO.[f]

History

Antiquity

According to Julius Caesar, the Belgae were the inhabitants of the northernmost part of Gaul. They lived in a region stretching from Paris to the Rhine, which is much bigger than modern Belgium. However, he also specifically used the Latin word "Belgium" to refer to a politically dominant part of that region, which is now in northernmost France.[28] In contrast, modern Belgium, together with neighbouring parts of the Netherlands and Germany, corresponds to the lands of the most northerly Belgae – the Morini, Menapii, Nervii, Germani Cisrhenani, and Aduatuci. Caesar found these peoples particularly warlike and economically undeveloped, and described them as kinsmen of the Germanic tribes east of the Rhine. The area around Arlon in southern Belgium was a part of the country of the powerful Treveri, to whom some of them paid tribute.

After Caesar's conquests, Gallia Belgica first came to be the Latin name of a large Roman province covering most of Northern Gaul, including the Belgae and Treveri. However, areas closer to the lower Rhine frontier, including the eastern part of modern Belgium, subsequently became part of the frontier province of Germania Inferior, which continued to interact with their neighbours outside the empire. At the time when central government collapsed in the Western Roman Empire, the Roman provinces of Belgica and Germania were inhabited by a mix of a Romanized population and Germanic-speaking Franks who came to dominate the military and political class.

Middle Ages

During the 5th century, the area came under the rule of the Frankish Merovingian kings, who initially established a kingdom ruling over the Romanized population in what is now northern France, and then conquered the other Frankish kingdoms. During the 8th century, the empire of the Franks came to be ruled by the Carolingian dynasty, whose centre of power included the area which is now eastern Belgium.[29] Over the centuries, it was divided up in many ways, but the Treaty of Verdun in 843 divided the Carolingian Empire into three kingdoms whose borders had a lasting impact on medieval political boundaries. Most of modern Belgium was in the Middle Kingdom, later known as Lotharingia, but the coastal county of Flanders, west of the Scheldt, became the northernmost part of West Francia, the predecessor of France. In 870 in the Treaty of Meerssen, modern Belgium lands all became part of the western kingdom for a period, but in 880 in the Treaty of Ribemont, Lotharingia came under the lasting control of the eastern kingdom, which became the Holy Roman Empire. The lordships and bishoprics along the "March" (frontier) between the two great kingdoms maintained important connections between each other. For example, the county of Flanders expanded over the Scheldt into the empire, and during several periods was ruled by the same lords as the county of Hainaut.

In the 13th and 14th centuries, the cloth industry and commerce boomed especially in the County of Flanders and it became one of the richest areas in Europe. This prosperity played a role in conflicts between Flanders and the king of France. Famously, Flemish militias scored a surprise victory at the Battle of the Golden Spurs against a strong force of mounted knights in 1302, but France soon regained control of the rebellious province.

Burgundian and Habsburg Netherlands

In the 15th century, the Duke of Burgundy in France took control of Flanders, and from there proceeded to unite much of what is now the Benelux, the so-called Burgundian Netherlands.[30] "Burgundy" and "Flanders" were the first two common names used for the Burgundian Netherlands which was the predecessor of the Austrian Netherlands, the predecessor of modern Belgium.[31] The union, technically stretching between two kingdoms, gave the area economic and political stability which led to an even greater prosperity and artistic creation.

Born in Belgium, the Habsburg Emperor Charles V was heir of the Burgundians, but also of the royal families of Austria, Castile and Aragon. With the Pragmatic Sanction of 1549 he gave the Seventeen Provinces more legitimacy as a stable entity, rather than just a temporary personal union. He also increased the influence of these Netherlands over the Prince-Bishopric of Liège, which continued to exist as a large semi-independent enclave.[32]

Spanish and Austrian Netherlands

The Eighty Years' War (1568–1648) was triggered by the Spanish government's policy towards Protestantism, which was becoming popular in the Low Countries. The rebellious northern United Provinces (Belgica Foederata in Latin, the "Federated Netherlands") eventually separated from the Southern Netherlands (Belgica Regia, the "Royal Netherlands"). The southern part continued to be ruled successively by the Spanish (Spanish Netherlands) and the Austrian House of Habsburgs (Austrian Netherlands) and comprised most of modern Belgium. This was the theatre of several more protracted conflicts during much of the 17th and 18th centuries involving France, including the Franco-Dutch War (1672–1678), the Nine Years' War (1688–1697), the War of the Spanish Succession (1701–1714), and part of the War of the Austrian Succession (1740–1748).

French Revolution and United Kingdom of the Netherlands

Following the campaigns of 1794 in the French Revolutionary Wars, the Low Countries – including territories that were never nominally under Habsburg rule, such as the Prince-Bishopric of Liège – were annexed by the French First Republic, ending Austrian rule in the region. A reunification of the Low Countries as the United Kingdom of the Netherlands occurred at the dissolution of the First French Empire in 1814, after the abdication of Napoleon.

Independent Belgium

In 1830, the Belgian Revolution led to the re-separation of the Southern Provinces from the Netherlands and to the establishment of a Catholic and bourgeois, officially French-speaking and neutral, independent Belgium under a provisional government and a national congress.[33][34] Since the installation of Leopold I as king on 21 July 1831, now celebrated as Belgium's National Day, Belgium has been a constitutional monarchy and parliamentary democracy, with a laicist constitution based on the Napoleonic code.[35] Although the franchise was initially restricted, universal suffrage for men was introduced after the general strike of 1893 (with plural voting until 1919) and for women in 1949.

The main political parties of the 19th century were the Catholic Party and the Liberal Party, with the Belgian Labour Party emerging towards the end of the 19th century. French was originally the official language used by the nobility and the bourgeoisie, especially after the rejection of the Dutch monarchy. French progressively lost its dominance as Dutch began to recover its status. This recognition became official in 1898, and in 1967, the parliament accepted a Dutch version of the Constitution.[36]

The Berlin Conference of 1885 ceded control of the Congo Free State to King Leopold II as his private possession. From around 1900 there was growing international concern for the extreme and savage treatment of the Congolese population under Leopold II, for whom the Congo was primarily a source of revenue from ivory and rubber production.[37] Many Congolese were killed by Leopold's agents for failing to meet production quotas for ivory and rubber.[38] In 1908, this outcry led the Belgian state to assume responsibility for the government of the colony, henceforth called the Belgian Congo.[39] A Belgian commission in 1919 estimated that Congo's population was half what it was in 1879.[38]

Germany invaded Belgium in August 1914 as part of the Schlieffen Plan to attack France, and much of the Western Front fighting of World War I occurred in western parts of the country. The opening months of the war were known as the Rape of Belgium due to German excesses. Belgium assumed control of the German colonies of Ruanda-Urundi (modern-day Rwanda and Burundi) during the war, and in 1924 the League of Nations mandated them to Belgium. In the aftermath of the First World War, Belgium annexed the Prussian districts of Eupen and Malmedy in 1925, thereby causing the presence of a German-speaking minority.

German forces again invaded the country in May 1940, and 40,690 Belgians, over half of them Jews, were killed during the subsequent occupation and the Holocaust. From September 1944 to February 1945 the Allies liberated Belgium. After World War II, a general strike forced King Leopold III to abdicate in 1951 in favour of his son, Prince Baudouin, since many Belgians thought he had collaborated with Germany during the war.[40] The Belgian Congo gained independence in 1960 during the Congo Crisis;[41] Ruanda-Urundi followed with its independence two years later. Belgium joined NATO as a founding member and formed the Benelux group of nations with the Netherlands and Luxembourg.

Belgium became one of the six founding members of the European Coal and Steel Community in 1951 and of the European Atomic Energy Community and European Economic Community, established in 1957. The latter has now become the European Union, for which Belgium hosts major administrations and institutions, including the European Commission, the Council of the European Union and the extraordinary and committee sessions of the European Parliament.

In the early 1990s, Belgium saw several large corruption scandals notably surrounding Marc Dutroux, Andre Cools, the Dioxin Affair, Agusta Scandal and the murder of Karel van Noppen.[42]

Geography

Belgium shares borders with France (620 km), Germany (162/167 km), Luxembourg (148 km), and the Netherlands (450 km). Its total surface, including water area, is 30,689 km2 (11,849 sq mi).[4] Before 2018, its total area was believed to be 30,528 km2 (11,787 sq mi). However, when the country's statistics were measured in 2018, a new calculation method was used. Unlike previous calculations, this one included the area from the coast to the low-water line, revealing the country to be 160 km2 (62 sq mi) larger in surface area than previously thought.[43][44] Its land area alone is 30,494 square kilometers.[5] It lies between latitudes 49°30' and 51°30' N, and longitudes 2°33' and 6°24' E.[45]

Belgium has three main geographical regions; the coastal plain in the northwest and the central plateau both belong to the Anglo-Belgian Basin, and the Ardennes uplands in the southeast to the Hercynian orogenic belt. The Paris Basin reaches a small fourth area at Belgium's southernmost tip, Belgian Lorraine.[46]

The coastal plain consists mainly of sand dunes and polders. Further inland lies a smooth, slowly rising landscape irrigated by numerous waterways, with fertile valleys and the northeastern sandy plain of the Campine (Kempen). The thickly forested hills and plateaus of the Ardennes are more rugged and rocky with caves and small gorges. Extending westward into France, this area is eastwardly connected to the Eifel in Germany by the High Fens plateau, on which the Signal de Botrange forms the country's highest point at 694 m (2,277 ft).[47][48]

The climate is maritime temperate with significant precipitation in all seasons (Köppen climate classification: Cfb), like most of northwest Europe.[49] The average temperature is lowest in January at 3 °C (37.4 °F) and highest in July at 18 °C (64.4 °F). The average precipitation per month varies between 54 mm (2.1 in) for February and April, to 78 mm (3.1 in) for July.[50] Averages for the years 2000 to 2006 show daily temperature minimums of 7 °C (44.6 °F) and maximums of 14 °C (57.2 °F) and monthly rainfall of 74 mm (2.9 in); these are about 1 °C and nearly 10 millimeters above last century's normal values, respectively.[51]

Climate change in Belgium has caused temperatures rises and more frequent and intense heatwaves, increases in winter rainfall and decreases in snowfall.[52] By 2100, sea levels along the Belgian coast are projected to rise by 60 to 90 cm with a maximum potential increase of up to 200 cm in the worst-case scenario.[53] The costs of climate change are estimated to amount to €9.5 billion a year in 2050 (2% of Belgian GDP), mainly due to extreme heat, drought and flooding, while economics gains due to milder winters amount to approximately €3 billion a year (0.65% of GDP).[53] In 2023, Belgium emitted 106.82 million tonnes of greenhouse gases (around 0.2% of the global total emissions), equivalent to 9.12 tonnes per person.[54][55] The country has committed to net zero by 2050.[56]

Phytogeographically, Belgium is shared between the Atlantic European and Central European provinces of the Circumboreal Region within the Boreal Kingdom.[57] According to the World Wide Fund for Nature, the territory of Belgium belongs to the terrestrial ecoregions of Atlantic mixed forests and Western European broadleaf forests.[58][59] Belgium had a 2018 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 1.36/10, ranking it 163rd globally out of 172 countries.[60] In Belgium forest cover is around 23% of the total land area, equivalent to 689,300 hectares (ha) of forest in 2020, up from 677,400 hectares (ha) in 1990. In 2020, naturally regenerating forest covered 251,200 hectares (ha) and planted forest covered 438,200 hectares (ha). For the year 2015, 47% of the forest area was reported to be under public ownership, 53% private ownership and 0% with ownership listed as other or unknown.[61][62]

Provinces

The territory of Belgium is divided into three Regions, two of which, the Flemish Region and Walloon Region, are in turn subdivided into provinces; the third Region, the Brussels Capital Region, is neither a province nor a part of a province.

| Province | Dutch name | French name | German name | Capital | Area[4] | Population (1 January 2024)[7] |

Density | ISO 3166-2:BE [63] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flemish Region | ||||||||||

| Antwerpen | Anvers | Antwerpen | Antwerp | 2,876 km2 (1,110 sq mi) | 1,926,522 | 670/km2 (1,700/sq mi) | VAN | |||

| Oost-Vlaanderen | Flandre orientale | Ostflandern | Ghent | 3,007 km2 (1,161 sq mi) | 1,572,002 | 520/km2 (1,300/sq mi) | VOV | |||

| Vlaams-Brabant | Brabant flamand | Flämisch-Brabant | Leuven | 2,118 km2 (818 sq mi) | 1,196,773 | 570/km2 (1,500/sq mi) | VBR | |||

| Limburg | Limbourg | Limburg | Hasselt | 2,427 km2 (937 sq mi) | 900,098 | 370/km2 (960/sq mi) | VLI | |||

| West-Vlaanderen | Flandre occidentale | Westflandern | Bruges | 3,197 km2 (1,234 sq mi) | 1,226,375 | 380/km2 (980/sq mi) | VWV | |||

| Walloon Region | ||||||||||

| Henegouwen | Hainaut | Hennegau | Mons | 3,813 km2 (1,472 sq mi) | 1,360,074 | 360/km2 (930/sq mi) | WHT | |||

| Luik | Liège | Lüttich | Liège | 3,857 km2 (1,489 sq mi) | 1,119,038 | 290/km2 (750/sq mi) | WLG | |||

| Luxemburg | Luxembourg | Luxemburg | Arlon | 4,459 km2 (1,722 sq mi) | 295,146 | 66/km2 (170/sq mi) | WLX | |||

| Namen | Namur | Namur (Namür) | Namur | 3,675 km2 (1,419 sq mi) | 503,895 | 140/km2 (360/sq mi) | WNA | |||

| Waals-Brabant | Brabant wallon | Wallonisch-Brabant | Wavre | 1,097 km2 (424 sq mi) | 414,130 | 380/km2 (980/sq mi) | WBR | |||

| Brussels Capital Region | ||||||||||

| Brussels Hoofdstedelijk Gewest | Région de Bruxelles-Capitale | Region Brüssel-Hauptstadt | Brussels City | 162 km2 (63 sq mi) | 1,249,597 | 7,700/km2 (20,000/sq mi) | BBR | |||

| Total | België | Belgique | Belgien | Brussels City | 30,689 km2 (11,849 sq mi) | 11,763,650 | 383/km2 (990/sq mi) | |||

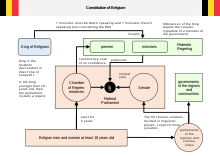

Politics and government

Belgium is a constitutional, popular monarchy and a federal parliamentary democracy. The bicameral federal parliament is composed of a Senate and a Chamber of Representatives. The former is made up of 50 senators appointed by the parliaments of the communities and regions and 10 co-opted senators. Prior to 2014, most of the Senate's members were directly elected. The Chamber's 150 representatives are elected under a proportional voting system from 11 electoral districts. Belgium has compulsory voting and thus maintains one of the highest rates of voter turnout in the world.[64]

The King (currently Philippe) is the head of state, though with limited prerogatives. He appoints ministers, including a Prime Minister, that have the confidence of the Chamber of Representatives to form the federal government. The Council of Ministers is composed of no more than fifteen members. With the possible exception of the Prime Minister, the Council of Ministers is composed of an equal number of Dutch-speaking members and French-speaking members.[65] The judicial system is based on civil law and originates from the Napoleonic code. The Court of Cassation is the court of last resort, with the courts of appeal one level below.[66]

Political culture

Belgium's political institutions are complex; most political power rests on representation of the main cultural communities.[67] Since about 1970, the significant national Belgian political parties have split into distinct components that mainly represent the political and linguistic interests of these communities.[68] The major parties in each community, though close to the political center, belong to three main groups: Christian Democrats, Liberals, and Social Democrats.[69] Further notable parties came into being well after the middle of last century, mainly to represent linguistic, nationalist, or environmental interests, and recently smaller ones of some specific liberal nature.[68]

A string of Christian Democrat coalition governments from 1958 was broken in 1999 after the first dioxin crisis, a major food contamination scandal.[70][71][72] A "rainbow coalition" emerged from six parties: the Flemish and the French-speaking Liberals, Social Democrats and Greens.[73] Later, a "purple coalition" of Liberals and Social Democrats formed after the Greens lost most of their seats in the 2003 election.[74]

The government led by Prime Minister Guy Verhofstadt from 1999 to 2007 achieved a balanced budget, some tax reforms, a labor-market reform, scheduled nuclear phase-out and instigated legislation allowing more stringent war crime and more lenient soft drug usage prosecution. Restrictions on euthanasia were reduced, and in 2003, Belgium became one of the first countries in the world to legalise same-sex marriage.[75] The government promoted active diplomacy in Africa[76] and opposed the invasion of Iraq.[77] It is the only country that does not have age restrictions on euthanasia.[78]

Verhofstadt's coalition fared badly in the June 2007 elections. For more than a year, the country experienced a political crisis.[79] This crisis was such that many observers speculated on a possible partition of Belgium.[80][81][82] From 21 December 2007 until 20 March 2008 the temporary Verhofstadt III Government was in office. This was a coalition of the Flemish and Francophone Christian Democrats, the Flemish and Francophone Liberals together with the Francophone Social Democrats.[83]

On that day a new government, led by Flemish Christian Democrat Yves Leterme, the actual winner of the federal elections of June 2007, was sworn in by the king. On 15 July 2008 Leterme offered the resignation of the cabinet to the king, as no progress in constitutional reforms had been made.[83] In December 2008, Leterme once more offered his resignation after a crisis surrounding the sale of Fortis to BNP Paribas.[84] At this juncture, his resignation was accepted and Christian Democratic and Flemish Herman Van Rompuy was sworn in as Prime Minister on 30 December 2008.[85]

After Herman Van Rompuy was designated the first permanent President of the European Council on 19 November 2009, he offered the resignation of his government to King Albert II on 25 November 2009. A few hours later, the new government under Prime Minister Yves Leterme was sworn in. On 22 April 2010, Leterme again offered the resignation of his cabinet to the king[86] after one of the coalition partners, the OpenVLD, withdrew from the government, and on 26 April 2010 King Albert officially accepted the resignation.[87]

The Parliamentary elections in Belgium on 13 June 2010 saw the Flemish nationalist N-VA become the largest party in Flanders, and the Socialist Party PS the largest party in Wallonia.[88] Until December 2011, Belgium was governed by Leterme's caretaker government awaiting the end of the deadlocked negotiations for formation of a new government. By 30 March 2011, this set a new world record for the elapsed time without an official government, previously held by war-torn Iraq.[89] Finally, in December 2011 the Di Rupo Government led by Walloon socialist Prime Minister Elio Di Rupo was sworn in.[90]

The 2014 federal election (coinciding with the regional elections) resulted in a further electoral gain for the Flemish nationalist N-VA, although the incumbent coalition (composed of Flemish and French-speaking Social Democrats, Liberals, and Christian Democrats) maintains a solid majority in Parliament and in all electoral constituencies. On 22 July 2014, King Philippe nominated Charles Michel (MR) and Kris Peeters (CD&V) to lead the formation of a new federal cabinet composed of the Flemish parties N-VA, CD&V, Open Vld and the French-speaking MR, which resulted in the Michel Government. It was the first time N-VA was part of the federal cabinet, while the French-speaking side was represented only by the MR, which achieved a minority of the public votes in Wallonia.[91]

In May 2019 federal elections in the Flemish-speaking northern region of Flanders far-right Vlaams Belang party made major gains. In the French-speaking southern area of Wallonia the Socialists were strong. The moderate Flemish nationalist party the N-VA remained the largest party in parliament.[92] In July 2019 prime minister Charles Michel was selected to hold the post of President of the European Council.[93] His successor Sophie Wilmès was Belgium's first female prime minister. She led the caretaker government since October 2019.[94] The Flemish Liberal party politician Alexander De Croo became new prime minister in October 2020. The parties had agreed on federal government 16 months after the elections.[95]

Communities and regions

Following a usage which can be traced back to the Burgundian and Habsburg courts,[96] in the 19th century it was necessary to speak French to belong to the governing upper class, and those who could only speak Dutch were effectively second-class citizens.[97] Late that century, and continuing into the 20th century, Flemish movements evolved to counter this situation.[98]

While the people in Southern Belgium spoke French or dialects of French, and most Brusselers adopted French as their first language, the Flemings refused to do so and succeeded progressively in making Dutch an equal language in the education system.[98] Following World War II, Belgian politics became increasingly dominated by the autonomy of its two main linguistic communities.[99] Intercommunal tensions rose and the constitution was amended to minimize the potential for conflict.[99]

Based on the four language areas defined in 1962–63 (the Dutch, bilingual, French and German language areas), consecutive revisions of the country's constitution in 1970, 1980, 1988 and 1993 established a unique form of a federal state with segregated political power into three levels:[100][101]

- The federal government, based in Brussels.

- The three language communities:

- the Flemish Community (Dutch-speaking);

- the French Community (French-speaking);[g]

- the German-speaking Community.

- The three regions:

- the Flemish Region, subdivided into five provinces;

- the Walloon Region, subdivided into five provinces;

- the Brussels-Capital Region.

The constitutional language areas determine the official languages in their municipalities, as well as the geographical limits of the empowered institutions for specific matters.[104] Although this would allow for seven parliaments and governments when the Communities and Regions were created in 1980, Flemish politicians decided to merge both.[105] Thus the Flemings just have one single institutional body of parliament and government is empowered for all except federal and specific municipal matters.[h]

The overlapping boundaries of the Regions and Communities have created two notable peculiarities: the territory of the Brussels-Capital Region (which came into existence nearly a decade after the other regions) is included in both the Flemish and French Communities, and the territory of the German-speaking Community lies wholly within the Walloon Region. Conflicts about jurisdiction between the bodies are resolved by the Constitutional Court of Belgium. The structure is intended as a compromise to allow different cultures to live together peacefully.[19]

Locus of policy jurisdiction

The Federal State's authority includes justice, defense, federal police, social security, nuclear energy, monetary policy and public debt, and other aspects of public finances. State-owned companies include the Belgian Post Group and Belgian Railways. The Federal Government is responsible for the obligations of Belgium and its federalized institutions towards the European Union and NATO. It controls substantial parts of public health, home affairs and foreign affairs.[106] The budget—without the debt—controlled by the federal government amounts to about 50% of the national fiscal income. The federal government employs around 12% of the civil servants.[107]

Communities exercise their authority only within linguistically determined geographical boundaries, originally oriented towards the individuals of a Community's language: culture (including audiovisual media), education and the use of the relevant language. Extensions to personal matters less directly connected with language comprise health policy (curative and preventive medicine) and assistance to individuals (protection of youth, social welfare, aid to families, immigrant assistance services, and so on.).[108]

Regions have authority in fields that can be broadly associated with their territory. These include economy, employment, agriculture, water policy, housing, public works, energy, transport, the environment, town and country planning, nature conservation, credit and foreign trade. They supervise the provinces, municipalities and intercommunal utility companies.[109]

In several fields, the different levels each have their own say on specifics. With education, for instance, the autonomy of the Communities neither includes decisions about the compulsory aspect nor allows for setting minimum requirements for awarding qualifications, which remain federal matters.[106] Each level of government can be involved in scientific research and international relations associated with its powers. The treaty-making power of the Regions' and Communities' Governments is the broadest of all the Federating units of all the Federations all over the world.[110][111][112]

Foreign relations

Because of its location at the crossroads of Western Europe, Belgium has historically been the route of invading armies from its larger neighbors. With virtually defenseless borders, Belgium has traditionally sought to avoid domination by the more powerful nations which surround it through a policy of mediation. The Belgians have been strong advocates of European integration. The headquarters of NATO and of several of the institutions of the European Union are located in Belgium.

Armed forces

The Belgian Armed Forces had 23,200 active personnel in 2023, including 8,500 in the Land Component, 1,400 in the Naval Component, 4,900 in the Air Component, 1,450 in the Medical Component, and 6,950 in joint service, in addition to 5,900 reserve personnel.[113] In 2019, Belgium's defense budget totaled €4.303 billion ($4.921 billion) representing .93% of its GDP.[114] The operational commands of the four components are subordinate to the Staff Department for Operations and Training of the Ministry of Defense, which is headed by the Assistant Chief of Staff Operations and Training, and to the Chief of Defense.[115] The Belgian military consists of volunteers (conscription was abolished in 1995), and citizens of other EU states, Iceland, Norway, Switzerland, or Lichtenstein are also able to join. Belgium has troops deployed in several African countries as part of UN or EU missions, in Iraq for the war against the Islamic State, and in eastern Europe for the NATO presence there.[113][116]

The effects of the Second World War made collective security a priority for Belgian foreign policy. In March 1948 Belgium signed the Treaty of Brussels and then joined NATO in 1948. However, the integration of the armed forces into NATO did not begin until after the Korean War.[117] The Belgians, along with the Luxembourg government, sent a detachment of battalion strength to fight in Korea known as the Belgian United Nations Command. This mission was the first in a long line of UN missions which the Belgians supported. Currently, the Belgian Marine Component is working closely together with the Dutch Navy under the command of the Admiral Benelux.

According to the 2024 Global Peace Index, Belgium is the 16th most peaceful country in the world.[118]

Economy

Belgium's strongly globalized economy[119] and its transport infrastructure are integrated with the rest of Europe. Its location at the heart of a highly industrialized region helped make it the world's 15th largest trading nation in 2007.[120][121] The economy is characterized by a highly productive work force, high GNP and high exports per capita.[122] Belgium's main imports are raw materials, machinery and equipment, chemicals, raw diamonds, pharmaceuticals, foodstuffs, transportation equipment, and oil products. Its main exports are machinery and equipment, chemicals, finished diamonds, metals and metal products, and foodstuffs.[123]

The Belgian economy is heavily service-oriented and shows a dual nature: a dynamic Flemish economy and a Walloon economy that lags behind.[19][124][i] One of the founding members of the European Union, Belgium strongly supports an open economy and the extension of the powers of EU institutions to integrate member economies. Since 1922, through the Belgium-Luxembourg Economic Union, Belgium and Luxembourg have been a single trade market with customs and currency union.[125]

Belgium was the first continental European country to undergo the Industrial Revolution, in the early 19th century.[126] Areas in Liège Province and around Charleroi rapidly developed mining and steelmaking, which flourished until the mid-20th century in the Sambre and Meuse valley and made Belgium one of the three most industrialized nations in the world from 1830 to 1910.[127][128] However, by the 1840s the textile industry of Flanders was in severe crisis, and the region experienced famine from 1846 to 1850.[129][130]

After World War II, Ghent and Antwerp experienced a rapid expansion of the chemical and petroleum industries. The 1973 and 1979 oil crises sent the economy into a recession; it was particularly prolonged in Wallonia, where the steel industry had become less competitive and experienced a serious decline.[131] In the 1980s and 1990s, the economic center of the country continued to shift northwards and is now concentrated in the populous Flemish Diamond area.[132]

By the end of the 1980s, Belgian macroeconomic policies had resulted in a cumulative government debt of about 120% of GDP. As of 2006[update], the budget was balanced and public debt was equal to 90.30% of GDP.[133] In 2005 and 2006, real GDP growth rates of 1.5% and 3.0%, respectively, were slightly above the average for the Euro area. Unemployment rates of 8.4% in 2005 and 8.2% in 2006 were close to the area average. By October 2010, this had grown to 8.5% compared to an average rate of 9.6% for the European Union as a whole (EU 27).[134][135] From 1832 until 2002, Belgium's currency was the Belgian franc. Belgium switched to the euro in 2002, with the first sets of euro coins being minted in 1999. The standard Belgian euro coins designated for circulation show the portrait of the monarch (first King Albert II, since 2013 King Philippe).

Despite an 18% decrease observed from 1970 to 1999, Belgium still had in 1999 the highest rail network density within the European Union with 113.8 km/1 000 km2. On the other hand, the same period, 1970–1999, has seen a huge growth (+56%) of the motorway network. In 1999, the density of km motorways per 1000 km2 and 1000 inhabitants amounted to 55.1 and 16.5 respectively and were significantly superior to the EU's means of 13.7 and 15.9.[136]

From a biological resource perspective, Belgium has a low endowment: Belgium's biocapacity adds up to only 0.8 global hectares in 2016,[137] just about half of the 1.6 global hectares of biocapacity available per person worldwide.[138] In contrast, in 2016, Belgians used on average 6.3 global hectares of biocapacity - their ecological footprint of consumption. This means they required about eight times as much biocapacity as Belgium contains. As a result, Belgium was running a biocapacity deficit of 5.5 global hectares per person in 2016.[137]

Belgium experiences some of the most congested traffic in Europe. In 2010, commuters to the cities of Brussels and Antwerp spent respectively 65 and 64 hours a year in traffic jams.[139] Like in most small European countries, more than 80% of the airways traffic is handled by a single airport, the Brussels Airport. The ports of Antwerp and Zeebrugge (Bruges) share more than 80% of Belgian maritime traffic, Antwerp being the second European harbor with a gross weight of goods handled of 115 988 000 t in 2000 after a growth of 10.9% over the preceding five years.[136][140] In 2016, the port of Antwerp handled 214 million tons after a year-on-year growth of 2.7%.[141]

There is a large economic gap between Flanders and Wallonia. Wallonia was historically wealthy compared to Flanders, mostly due to its heavy industries, but the decline of the steel industry post-World War II led to the region's rapid decline, whereas Flanders rose swiftly. Since then, Flanders has been prosperous, among the wealthiest regions in Europe, whereas Wallonia has been languishing. As of 2007, the unemployment rate of Wallonia is over double that of Flanders. The divide has played a key part in the tensions between the Flemish and Walloons in addition to the already-existing language divide. Pro-independence movements have gained high popularity in Flanders as a consequence. The separatist New Flemish Alliance (N-VA) party, for instance, is the largest party in Belgium.[142][143][144]

Science and technology

Contributions to the development of science and technology have appeared throughout the country's history. The 16th century Early Modern flourishing of Western Europe included cartographer Gerardus Mercator, anatomist Andreas Vesalius, herbalist Rembert Dodoens[145][146][147][148] and mathematician Simon Stevin among the most influential scientists.[149]

Chemist Ernest Solvay[150] and engineer Zenobe Gramme (École industrielle de Liège)[151] gave their names to the Solvay process and the Gramme dynamo, respectively, in the 1860s. Bakelite was developed in 1907–1909 by Leo Baekeland. Ernest Solvay also acted as a major philanthropist and gave his name to the Solvay Institute of Sociology, the Solvay Brussels School of Economics and Management and the International Solvay Institutes for Physics and Chemistry which are now part of the Université libre de Bruxelles. In 1911, he started a series of conferences, the Solvay Conferences on Physics and Chemistry, which have had a deep impact on the evolution of quantum physics and chemistry.[152] A major contribution to fundamental science was also due to a Belgian, Monsignor Georges Lemaître (Catholic University of Louvain), who is credited with proposing the Big Bang theory of the origin of the universe in 1927.[153]

Three Nobel Prizes in Physiology or Medicine were awarded to Belgians: Jules Bordet (Université libre de Bruxelles) in 1919, Corneille Heymans (University of Ghent) in 1938 and Albert Claude (Université libre de Bruxelles) together with Christian de Duve (Université catholique de Louvain) in 1974. François Englert (Université libre de Bruxelles) was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2013. Ilya Prigogine (Université libre de Bruxelles) was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1977.[154] Two Belgian mathematicians have been awarded the Fields Medal: Pierre Deligne in 1978 and Jean Bourgain in 1994.[155][156] Belgium was ranked 24th in the Global Innovation Index in 2024.[157]

Demographics

As of 1 January 2024, the total population of Belgium according to its population register was 11,763,650.[7] The population density of Belgium is 383/km2 (990/sq mi) as of January 2024, making it the 22nd most densely populated country in the world, and the 6th most densely populated country in Europe. The most densely populated province is Antwerp, the least densely populated province is Luxembourg. As of January 2024, the Flemish Region (Flanders) had a population of 6,821,770 (58.0% of Belgium), its most populous cities being Antwerp (545,000), Ghent (270,000), and Bruges (120,000). The Walloon Region (Wallonia) had a population of 3,692,283 (31.4% of Belgium), its most populous cities being Charleroi (204,000), Liège (196,000), and Namur (114,000). The Brussels-Capital Region (Brussels) had a population of 1,249,597 (10.6% of Belgium), existing of 19 municipalities, its most populous cities being the city of Brussels (197,000), Schaerbeek (130,000), and Anderlecht (127,000).[7]

In 2017 the average total fertility rate (TFR) across Belgium was 1.64 children per woman, below the replacement rate of 2.1; it remains considerably below the high of 4.87 children born per woman in 1873.[158] Belgium subsequently has one of the oldest populations in the world, with an average age of 41.6 years.[159]

Migration

As of 2007[update], nearly 92% of the population had Belgian citizenship,[160] and other European Union member citizens account for around 6%. The prevalent foreign nationals were Italian (171,918), French (125,061), Dutch (116,970), Moroccan (80,579), Portuguese (43,509), Spanish (42,765), Turkish (39,419) and German (37,621).[161][162] In 2007, there were 1.38 million foreign-born residents in Belgium, corresponding to 12.9% of the total population. Of these, 685,000 (6.4%) were born outside the EU and 695,000 (6.5%) were born in another EU Member State.[163][164]

At the beginning of 2012, people of foreign background and their descendants were estimated to have formed around 25% of the total population i.e. 2.8 million new Belgians.[165] Of these new Belgians, 1,200,000 are of European ancestry and 1,350,000[166] are from non-Western countries (most of them from Morocco, Turkey, and the DR Congo). Since the modification of the Belgian nationality law in 1984 more than 1.3 million migrants have acquired Belgian citizenship. The largest group of immigrants and their descendants in Belgium are Italian Belgians and Moroccan Belgians.[167] 89.2% of inhabitants of Turkish origin have been naturalized, as have 88.4% of people of Moroccan background, 75.4% of Italians, 56.2% of the French and 47.8% of Dutch people.[166]

Statbel released figures of the Belgian population in relation to the origin of people in Belgium. According to the data, as of 1 January 2021, 67.3% of the Belgian population was of ethnic Belgian origin and 32.7% were of foreign origin or nationality, with 20.3% of those of a foreign nationality or ethnic group originating from neighbouring countries. The study also found that 74.5% of the Brussels Capital Region were of non-Belgian origin, of which 13.8% originated from neighbouring countries.[168]

Largest cities or towns in Belgium

Numbers according to the Belgium's National Register,[169] (1 January 2023) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name | Region | Pop. | Rank | Name | Region | Pop. | ||

Antwerp  Ghent |

1 | Antwerp | Flanders | 536,079 | 11 | Molenbeek-Saint-Jean/Sint-Jans-Molenbeek | Brussels | 97,610 |  Charleroi  Liège |

| 2 | Ghent | Flanders | 267,709 | 12 | Mons | Wallonia | 96,055 | ||

| 3 | Charleroi | Wallonia | 203,245 | 13 | Aalst | Flanders | 89,915 | ||

| 4 | Liège | Wallonia | 194,877 | 14 | Mechelen | Flanders | 88,463 | ||

| 5 | City of Brussels | Brussels | 192,950 | 15 | Ixelles/Elsene | Brussels | 88,081 | ||

| 6 | Schaerbeek/Schaarbeek | Brussels | 130,422 | 16 | Uccle/Ukkel | Brussels | 85,706 | ||

| 7 | Anderlecht | Brussels | 124,353 | 17 | La Louvière | Wallonia | 81,293 | ||

| 8 | Bruges | Flanders | 119,445 | 18 | Sint-Niklaas | Flanders | 81,066 | ||

| 9 | Namur | Wallonia | 113,174 | 19 | Hasselt | Flanders | 80,299 | ||

| 10 | Leuven | Flanders | 102,851 | 20 | Kortrijk | Flanders | 78,841 | ||

Languages

Belgium has three official languages: Dutch, French and German. A number of non-official minority languages are spoken as well.[170] As no census exists, there are no official statistical data regarding the distribution or usage of Belgium's three official languages or their dialects.[171] However, various criteria, including the language(s) of parents, of education, or the second-language status of foreign born, may provide suggested figures. An estimated 60% of the Belgian population are native speakers of Dutch (often referred to as Flemish), and 40% of the population speaks French natively. French-speaking Belgians are often referred to as Walloons, although the French speakers in Brussels are not Walloons.[j]

The total number of native Dutch speakers is estimated to be about 6.23 million, concentrated in the northern Flanders region, while native French speakers number 3.32 million in Wallonia and an estimated 870,000 (or 85%) in the officially bilingual Brussels-Capital Region.[k][172] The German-speaking Community is made up of 73,000 people in the east of the Walloon Region; around 10,000 German and 60,000 Belgian nationals are speakers of German. Roughly 23,000 more German speakers live in municipalities near the official Community.[173][174][175][176]

Both Belgian Dutch and Belgian French have minor differences in vocabulary and semantic nuances from the varieties spoken respectively in the Netherlands and France. Many Flemish people still speak dialects of Dutch in their local environment. Walloon, considered either as a dialect of French or a distinct Romance language,[177][178] is now only understood and spoken occasionally, mostly by elderly people. Walloon is divided into four dialects, which along with those of Picard,[179] are rarely used in public life and have largely been replaced by French.

Religion

The Constitution of Belgium provides for freedom of religion, and the government respects this right in practice.[180] Belgium officially recognizes three religions: Christianity (Catholic, Protestantism, Orthodox churches and Anglicanism), Islam and Judaism.[181] During the reigns of Albert I and Baudouin, the Belgian royal family had a reputation of deeply rooted Catholicism.[180]

Catholicism has traditionally been Belgium's majority religion; being especially strong in Flanders. However, by 2009 Sunday church attendance was 5% for Belgium in total; 3% in Brussels,[182] and 5.4% in Flanders. Church attendance in 2009 in Belgium was roughly half of the Sunday church attendance in 1998 (11% for the total of Belgium in 1998).[183] Despite the drop in church attendance, Catholic identity nevertheless remains an important part of Belgium's culture.[180]

According to the Eurobarometer 2010,[184] 37% of Belgian citizens believe in God, 31% in some sort of spirit or life-force. 27% do not believe in any sort of spirit, God, or life-force. 5% did not respond. According to the Eurobarometer 2015, 60.7% of the total population of Belgium adhered to Christianity, with Catholicism being the largest denomination with 52.9%. Protestants comprised 2.1% and Orthodox Christians were the 1.6% of the total. Non-religious people comprised 32.0% of the population and were divided between atheists (14.9%) and agnostics (17.1%). A further 5.2% of the population was Muslim and 2.1% were believers in other religions.[185] The same survey held in 2012 found that Christianity was the largest religion in Belgium, accounting for 65% of Belgians.[186]

In the early 2000s, there were approximately 42,000 Jews in Belgium. The Jewish Community of Antwerp (numbering some 18,000) is one of the largest in Europe, and one of the last places in the world where Yiddish is the primary language of a large Jewish community (mirroring certain Orthodox and Hasidic communities in New York, New Jersey, and Israel). In addition, most Jewish children in Antwerp receive a Jewish education.[187] There are several Jewish newspapers and more than 45 active synagogues (30 of which are in Antwerp) in the country. A 2006 inquiry in Flanders, considered to be a more religious region than Wallonia, showed that 55% considered themselves religious and that 36% believed that God created the universe.[188] On the other hand, Wallonia has become one of Europe's most secular/least religious regions. Most of the French-speaking region's population does not consider religion an important part of their lives, and as much as 45% of the population identifies as irreligious. This is particularly the case in eastern Wallonia and areas along the French border.

A 2008 estimate found that approximately 6% of the Belgian population (628,751 people) is Muslim. Muslims constitute 23.6% of the population of Brussels, 4.9% of Wallonia and 5.1% of Flanders. The majority of Belgian Muslims live in the major cities, such as Antwerp, Brussels and Charleroi. The largest group of immigrants in Belgium are Moroccans, with 400,000 people. The Turks are the third largest group, and the second largest Muslim ethnic group, numbering 220,000.[189][190]

Health

The Belgians enjoy good health. According to 2012 estimates, the average life expectancy is 79.65 years.[123] Since 1960, life expectancy has, in line with the European average, grown by two months per year. Death in Belgium is mainly due to heart and vascular disorders, neoplasms, disorders of the respiratory system and unnatural causes of death (accidents, suicide). Non-natural causes of death and cancer are the most common causes of death for females up to age 24 and males up to age 44.[191]

Healthcare in Belgium is financed through both social security contributions and taxation. Health insurance is compulsory. Health care is delivered by a mixed public and private system of independent medical practitioners and public, university and semi-private hospitals. Health care service are payable by the patient and reimbursed later by health insurance institutions, but for ineligible categories (of patients and services) so-called 3rd party payment systems exist.[191] The Belgian health care system is supervised and financed by the federal government, the Flemish and Walloon Regional governments; and the German Community also has (indirect) oversight and responsibilities.[191]

For the first time in Belgian history, the first child was euthanized following the 2-year mark of the removal of the euthanization age restrictions. The child had been euthanized due to an incurable disease that was inflicted upon the child. Although there may have been some support for the euthanization there is a possibility of controversy due to the issue revolving around the subject of assisted suicide.[192]

Excluding assisted suicide, Belgium has the highest suicide rate in Western Europe and one of the highest suicide rates in the developed world (exceeded only by Lithuania, South Korea, and Latvia).[193]

Education

Education is compulsory from 6 to 18 years of age for Belgians.[194] Among OECD countries in 2002, Belgium had the third highest proportion of 18- to 21-year-olds enrolled in postsecondary education, at 42%.[195] Though an estimated 99% of the adult population is literate, concern is rising over functional illiteracy.[179][196] The Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), coordinated by the OECD, currently ranks Belgium's education as the 19th best in the world, being significantly higher than the OECD average.[197] Education is organized separately by each community. The Flemish Community scores noticeably above the French and German-speaking Communities.[198]

Mirroring the structure of the 19th-century Belgian political landscape, characterized by the Liberal and the Catholic parties, the educational system is segregated into secular and religious schools. The secular branch of schooling is controlled by the communities, the provinces, or the municipalities, while religious, mainly Catholic branch education, is organized by religious authorities, which are also subsidized and supervised by the communities.[199]

Culture

Despite its political and linguistic divisions, the region corresponding to today's Belgium has seen the flourishing of major artistic movements that have had tremendous influence on European art and culture. Nowadays, to a certain extent, cultural life is concentrated within each language Community, and a variety of barriers have made a shared cultural sphere less pronounced.[19][200][201] Since the 1970s, there are no bilingual universities or colleges in the country except the Royal Military Academy and the Antwerp Maritime Academy.[202]

Fine arts

Contributions to painting and architecture have been especially rich. The Mosan art, the Early Netherlandish,[203] the Flemish Renaissance and Baroque painting[204] and major examples of Romanesque, Gothic, Renaissance and Baroque architecture[205] are milestones in the history of art. While the 15th century's art in the Low Countries is dominated by the religious paintings of Jan van Eyck and Rogier van der Weyden, the 16th century is characterized by a broader panel of styles such as Peter Breughel's landscape paintings and Lambert Lombard's representation of the antique.[206] Though the Baroque style of Peter Paul Rubens and Anthony van Dyck flourished in the early 17th century in the Southern Netherlands,[207] it gradually declined thereafter.[208][209]

During the 19th and 20th centuries many original romantic, expressionist and surrealist Belgian painters emerged, including James Ensor and other artists belonging to the Les XX group, Constant Permeke, Paul Delvaux and René Magritte. The avant-garde CoBrA movement appeared in the 1950s, while the sculptor Panamarenko remains a remarkable figure in contemporary art.[210][211] Multidisciplinary artists Jan Fabre, Wim Delvoye and the painter Luc Tuymans are other internationally renowned figures on the contemporary art scene.

Belgian contributions to architecture also continued into the 19th and 20th centuries, including the work of Victor Horta and Henry van de Velde, who were major initiators of the Art Nouveau style.[212][213]

The vocal music of the Franco-Flemish School developed in the southern part of the Low Countries and was an important contribution to Renaissance culture.[214] In the 19th and 20th centuries, there was an emergence of major violinists, such as Henri Vieuxtemps, Eugène Ysaÿe and Arthur Grumiaux, while Adolphe Sax invented the saxophone in 1846. The composer César Franck was born in Liège in 1822. Contemporary popular music in Belgium is also of repute. Jazz musicians Django Reinhardt and Toots Thielemans and singer Jacques Brel have achieved global fame. Nowadays, singer Stromae has been a musical revelation in Europe and beyond, having great success. In rock/pop music, Telex, Front 242, K's Choice, Hooverphonic, Zap Mama, Soulwax and dEUS are well known. In the heavy metal scene, bands like Machiavel, Channel Zero and Enthroned have a worldwide fan-base.[215]

Belgium has produced several well-known authors, including the poets Emile Verhaeren, Guido Gezelle, Robert Goffin and novelists Hendrik Conscience, Stijn Streuvels, Georges Simenon, Suzanne Lilar, Hugo Claus and Amélie Nothomb. The poet and playwright Maurice Maeterlinck won the Nobel Prize in literature in 1911. The Adventures of Tintin by Hergé is the best known of Franco-Belgian comics, but many other major authors, including Peyo (The Smurfs), André Franquin (Gaston Lagaffe), Dupa (Cubitus), Morris (Lucky Luke), Greg (Achille Talon), Lambil (Les Tuniques Bleues), Edgar P. Jacobs and Willy Vandersteen brought the Belgian cartoon strip industry a worldwide fame.[216] Additionally, famous crime author Agatha Christie created the character Hercule Poirot, a Belgian detective, who has served as a protagonist in a number of her acclaimed mystery novels.

Belgian cinema has brought a number of mainly Flemish novels to life on-screen.[l] Other Belgian directors include André Delvaux, Stijn Coninx, Luc and Jean-Pierre Dardenne; well-known actors include Jean-Claude Van Damme, Jan Decleir and Marie Gillain; and successful films include Bullhead, Man Bites Dog and The Alzheimer Affair.[217] Belgium is also home to a number of successful fashion designers Category:Belgian fashion designers.

Folklore

Folklore plays a major role in Belgium's cultural life; the country has a comparatively high number of processions, cavalcades, parades, ommegangs, ducasses,[m] kermesses, and other local festivals, nearly always with an originally religious or mythological background. The three-day Carnival of Binche, near Mons, with its famous Gilles (men dressed in high, plumed hats and bright costumes) is held just before Lent (the 40 days between Ash Wednesday and Easter). Together with the 'Processional Giants and Dragons' of Ath, Brussels, Dendermonde, Mechelen and Mons, it is recognized by UNESCO as a Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity.[218]

Other examples are the three-day Carnival of Aalst in February or March; the still very religious processions of the Holy Blood taking place in Bruges in May, the Virga Jesse procession held every seven years in Hasselt, the annual procession of Hanswijk in Mechelen, the 15 August festivities in Liège, and the Walloon festival in Namur. Originated in 1832 and revived in the 1960s, the Gentse Feesten (a music and theatre festival organized in Ghent around Belgian National Day, on 21 July) have become a modern tradition. Several of these festivals include sporting competitions, such as cycling, and many fall under the category of kermesses.

A major non-official holiday (which is however not an official public holiday) is Saint Nicholas Day (Dutch: Sinterklaas, French: la Saint-Nicolas), a festivity for children, and in Liège, for students.[219] It takes place each year on 6 December and is a sort of early Christmas. On the evening of 5 December, before going to bed, children put their shoes by the hearth with water or wine and a carrot for Saint Nicholas' horse or donkey. According to tradition, Saint Nicholas comes at night and travels down the chimney. He then takes the food and water or wine, leaves presents, goes back up, feeds his horse or donkey, and continues on his course. He also knows whether children have been good or bad. This holiday is especially loved by children in Belgium and the Netherlands. Dutch immigrants imported the tradition into the United States, where Saint Nicholas is now known as Santa Claus.

Cuisine

Belgium is famous for beer, chocolate, waffles and French fries. The national dishes are steak and fries, and mussels with fries.[220][221][222] Many highly ranked Belgian restaurants can be found in the most influential restaurant guides, such as the Michelin Guide.[223] One of the many beers with the high prestige is that of the Trappist monks. Technically, it is an ale and traditionally each abbey's beer is served in its own glass (the forms, heights and widths are different). There are only eleven breweries (six of them are Belgian) that are allowed to brew Trappist beer.

Although Belgian gastronomy is connected to French cuisine, some recipes were reputedly invented there, such as French fries (despite the name, although their exact place of origin is uncertain), Flemish Carbonade (a beef stew with beer, mustard and bay laurel), speculaas (or speculoos in French, a sort of cinnamon and ginger-flavoured shortcrust biscuit), Brussels waffles (and their variant, Liège waffles), waterzooi (a broth made with chicken or fish, cream and vegetables), endive with bechamel sauce, Brussels sprouts, Belgian pralines (Belgium has some of the most renowned chocolate houses), charcuterie (deli meats) and Paling in 't groen (river eels in a sauce of green herbs).

Brands of Belgian chocolate and pralines, like Côte d'Or, Neuhaus, Leonidas and Godiva are famous, as well as independent producers such as Burie and Del Rey in Antwerp and Mary's in Brussels.[224] Belgium produces over 1100 varieties of beer.[225][226] The Trappist beer of the Abbey of Westvleteren has repeatedly been rated the world's best beer.[227][228][229]

The biggest brewer in the world by volume is Anheuser-Busch InBev, based in Leuven.[230]

Sports

Since the 1970s, sports clubs and federations are organized separately within each language community.[231] The Administration de l'Éducation Physique et du Sport (ADEPS) is responsible for recognising the various French-speaking sports federations and also runs three sports centres in the Brussels-Capital Region.[232] Its Dutch-speaking counterpart is Sport Vlaanderen (formerly called BLOSO).[233]

Association football is the most popular sport in both parts of Belgium; also very popular are cycling, tennis, swimming, judo[234] and basketball.[235] The Belgium national football team has been among the best on the FIFA World Rankings ever since November 2015, when it reached the top spot for the first time.[236] Since the 1990s, the team has been the world's number one for the most years in history, only behind the records of Brazil and Spain.[237] The team's golden generations with the world class players in the squad, namely Eden Hazard, Kevin De Bruyne, Jean-Marie Pfaff, Jan Ceulemans achieved the bronze medals at World Cup 2018, and silver medals at Euro 1980. Belgium hosted the Euro 1972, and co-hosted the Euro 2000 with the Netherlands.

Belgians hold the most Tour de France victories of any country except France. They also have the most victories on the UCI Road World Championships. With five victories in the Tour de France and numerous other cycling records, Belgian cyclist Eddy Merckx is regarded as one of the greatest cyclists of all time.[238] Philippe Gilbert and Remco Evenepoel were the 2012 and 2022 world champions, respectively. Other well-known Belgian cyclists are Tom Boonen and Wout van Aert.

Kim Clijsters and Justine Henin both were Player of the Year in the Women's Tennis Association as they were ranked the number one female tennis player. The Spa-Francorchamps motor-racing circuit hosts the Formula One World Championship Belgian Grand Prix. The Belgian driver, Jacky Ickx, won eight Grands Prix and six 24 Hours of Le Mans and finished twice as runner-up in the Formula One World Championship. Belgium also has a strong reputation in, motocross with the riders Joël Robert, Roger De Coster, Georges Jobé, Eric Geboers and Stefan Everts, among others.[239]

Sporting events annually held in Belgium include the Memorial Van Damme athletics competition, the Belgian Grand Prix Formula One, and a number of classic cycle races such as the Tour of Flanders and Liège–Bastogne–Liège. The 1920 Summer Olympics were held in Antwerp. The 1977 European Basketball Championship was held in Liège and Ostend.

See also

Footnotes

- ^ Dutch: België [ˈbɛlɣijə] ⓘ; French: Belgique [bɛlʒik] ⓘ; German: Belgien [ˈbɛlɡi̯ən] ⓘ

- ^ Dutch: Koninkrijk België [ˈkoːnɪŋkˌrɛik ˈbɛlɣijə] ⓘ; French: Royaume de Belgique [ʁwa.jom də bɛl.ʒik] ⓘ; German: Königreich Belgien [ˈkøːnɪkˌʁaɪ̯ç ˈbɛlɡi̯ən] ⓘ

- ^ The Brussels-Capital Region, whose metropolitan area comprises the City of Brussels itself plus 18 independent municipal entities, counts over 1,700,000 inhabitants, but these communities are counted separately by the Belgian Statistics Office.[12]

- ^ The name "French Community" refers to Francophone Belgians, and not to French people residing in Belgium. As such, the French Community of Belgium is sometimes rendered in English as "the French-speaking Community of Belgium" for clarity.[15]

- ^ Between 1885 and 1908, the Congo Free State, which was privately owned by King Leopold II of Belgium, was characterized by widespread atrocities and disease; amid public outcry in Europe, Belgium annexed the territory as a colony.[22]

- ^ Belgium is a member of, or affiliated to, many international organizations, including ACCT, AfDB, AsDB, Australia Group, Benelux, BIS, CCC, CE, CERN, EAPC, EBRD, EIB, EMU, ESA, EU, FAO, G-10, IAEA, IBRD, ICAO, ICC, ICRM, IDA, IDB, IEA, IFAD, IFC, IFRCS, IHO, ILO, IMF, IMO, IMSO, Intelsat, Interpol, IOC, IOM, ISO, ITU, MONUSCO (observers), NATO, NEA, NSG, OAS (observer), OECD, OPCW, OSCE, PCA, UN, UNCTAD, UNECE, UNESCO, UNHCR, UNIDO, UNMIK, UNMOGIP, UNRWA, UNTSO, UPU, WADB (non-regional), WEU, WHO, WIPO, WMO, WTrO, ZC.

- ^ Since 2011, the French Community has used the name "Wallonia-Brussels Federation" (French: Fédération Wallonie-Bruxelles), which is controversial because its name in the Belgian Constitution has not changed and because it is seen as a political statement.[102][103]

- ^ The Constitution set out seven institutions each of which can have a parliament, government and administration. In fact, there are only six such bodies because the Flemish Region merged into the Flemish Community. This single Flemish body thus exercises powers about Community matters in the bilingual area of Brussels-Capital and in the Dutch language area, while about Regional matters only in Flanders.

- ^ The richest (per capita income) of Belgium's three regions is the Flemish Region, followed by the Walloon Region and lastly the Brussels-Capital Region. The ten municipalities with the highest reported income are: Laethem-Saint-Martin, Keerbergen, Lasne, Oud-Heverlee, Hove, De Pinte, Meise, Knokke-Heist, Bierbeek."Où habitent les Belges les plus riches?". trends.be. 2010. Archived from the original on 27 August 2011. Retrieved 15 July 2011.

- ^ Native speakers of Dutch living in Wallonia and of French in Flanders are relatively small minorities that furthermore largely balance one another, hence attributing all inhabitants of each unilingual area to the area's language can cause only insignificant inaccuracies (99% can speak the language). Dutch: Flanders' 6.079 million inhabitants and about 15% of Brussels' 1.019 million are 6.23 million or 59.3% of the 10.511 million inhabitants of Belgium (2006); German: 70,400 in the German-speaking Community (which has language facilities for its less than 5% French-speakers) and an estimated 20,000–25,000 speakers of German in the Walloon Region outside the geographical boundaries of their official Community, or 0.9%; French: in the latter area as well as mainly in the rest of Wallonia (3.321 million) and 85% of the Brussels inhabitants (0.866 million) thus 4.187 million or 39.8%; together indeed 100%.

- ^ Flemish Academic Eric Corijn (initiator of Charta 91), at a colloquium regarding Brussels, on 2001-12-05, states that in Brussels 91% of the population speaks French at home, either alone or with another language, and about 20% speaks Dutch at home, either alone (9%) or with French (11%)—After ponderation, the repartition can be estimated at between 85 and 90% French-speaking, and the remaining are Dutch-speaking, corresponding to the estimations based on languages chosen in Brussels by citizens for their official documents (ID, driving licenses, weddings, birth, sex, and so on); all these statistics on language are also available at Belgian Department of Justice (for weddings, birth, sex), Department of Transport (for Driving licenses), Department of Interior (for IDs), because there are no means to know precisely the proportions since Belgium has abolished 'official' linguistic censuses, thus official documents on language choices can only be estimations. For a web source on this topic, see e.g. General online sources: Janssens, Rudi

- ^ Notable Belgian films based on works by Flemish authors include: De Witte (author Ernest Claes) movie by Jan Vanderheyden and Edith Kiel in 1934, remake as De Witte van Sichem directed by Robbe De Hert in 1980; De man die zijn haar kort liet knippen (Johan Daisne) André Delvaux 1965; Mira ('De teleurgang van de Waterhoek' by Stijn Streuvels) Fons Rademakers 1971; Malpertuis (aka The Legend of Doom House) (Jean Ray [pen name of Flemish author who mainly wrote in French, or as John Flanders in Dutch]) Harry Kümel 1971; De loteling (Hendrik Conscience) Roland Verhavert 1974; Dood van een non (Maria Rosseels) Paul Collet and Pierre Drouot 1975; Pallieter (Felix Timmermans) Roland Verhavert 1976; De komst van Joachim Stiller (Hubert Lampo) Harry Kümel 1976; De Leeuw van Vlaanderen (Hendrik Conscience) Hugo Claus (a famous author himself) 1985; Daens ('Pieter Daens' by Louis Paul Boon) Stijn Coninx 1992; see also Filmarchief les DVD!s de la cinémathèque (in Dutch). Retrieved on 7 June 2007.

- ^ The Dutch word ommegang is here used in the sense of an entirely or mainly non-religious procession, or the non-religious part thereof—see also its article on the Dutch-language Wikipedia; the Processional Giants of Brussels, Dendermonde and Mechelen mentioned in this paragraph are part of each city's ommegang. The French word ducasse refers also to a procession; the mentioned Processional Giants of Ath and Mons are part of each city's ducasse.

References

- ^ "Diverity according to origin in Belgium". STATBEL.

- ^ "Data.europa.eu".

- ^ "Government type: Belgium". The World Factbook. CIA. Archived from the original on 7 February 2012. Retrieved 19 December 2011.

- ^ a b c d "Land use according to the land register". Statbel. 16 November 2023. Retrieved 31 July 2024.

- ^ a b "Land use". Statbel. 15 September 2023. Retrieved 31 July 2024.

- ^ "Surface water and surface water change". Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Archived from the original on 24 March 2021. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- ^ a b c d e "Structure of the Population". Statbel. 4 June 2024. Retrieved 31 July 2024.

- ^ a b c d "World Economic Outlook Database, October 2024 Edition. (Belgium)". www.imf.org. International Monetary Fund. 22 October 2024. Retrieved 26 October 2024.

- ^ "Gini coefficient of equivalised disposable income – EU-SILC survey". ec.europa.eu. Eurostat. Archived from the original on 9 October 2020. Retrieved 28 June 2023.

- ^ "Human Development Report 2023/24" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 13 March 2024. p. 288. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 March 2024. Retrieved 13 March 2024.

- ^ The Belgian Constitution (PDF). Brussels, Belgium: Belgian House of Representatives. May 2014. p. 63. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 August 2015. Retrieved 10 September 2015.

- ^ "Statbel the Belgian statistics office". Archived from the original on 16 May 2021. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- ^ Pateman, Robert and Elliott, Mark (2006). Belgium. Benchmark Books. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-7614-2059-0

- ^ The Belgian Constitution (PDF). Brussels, Belgium: Belgian House of Representatives. May 2014. p. 5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 August 2015. Retrieved 10 September 2015.

Article 3: Belgium comprises three Regions: the Flemish Region, the Walloon Region and the Brussels Region. Article 4: Belgium comprises four linguistic regions: the Dutch-speaking region, the French-speaking region, the bilingual region of Brussels-Capital and the German-speaking region.

- ^ "Belgium - French speaking community". portal.cor.europa.eu. Retrieved 30 September 2024.

- ^ Janssens, Rudi (2008). "Language use in Brussels and the position of Dutch". Brussels Studies. Brussels Studies [Online]. doi:10.4000/brussels.520. ISSN 2031-0293. Archived from the original on 17 July 2018. Retrieved 17 July 2018.

- ^ Leclerc, Jacques (18 January 2007). "Belgique • België • Belgien—Région de Bruxelles-Capitale • Brussels Hoofdstedelijk Gewest". L'aménagement linguistique dans le monde (in French). Host: Trésor de la langue française au Québec (TLFQ), Université Laval, Quebec. Archived from the original on 9 June 2007. Retrieved 18 June 2007.

C'est une région officiellement bilingue formant au centre du pays une enclave dans la province du Brabant flamand (Vlaams Brabant)

*"About Belgium". Belgian Federal Public Service (ministry) / Embassy of Belgium in the Republic of Korea. Archived from the original on 2 October 2008. Retrieved 21 June 2007.the Brussels-Capital Region is an enclave of 162 km2 within the Flemish region.

*"Flanders (administrative region)". Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia. Microsoft. 2007. Archived from the original on 15 June 2009. Retrieved 21 June 2007.The capital of Belgium, Brussels, is an enclave within Flanders.

*McMillan, Eric (October 1999). "The FIT Invasions of Mons" (PDF). Capital translator, Newsletter of the NCATA, Vol. 21, No. 7, p. 1. National Capital Area Chapter of the American Translators Association (NCATA). Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 June 2007. Retrieved 21 June 2007.The country is divided into three autonomous regions: Dutch-speaking Flanders in the north, mostly French-speaking Brussels in the center as an enclave within Flanders and French-speaking Wallonia in the south, including the German-speaking Cantons de l'Est.

*Van de Walle, Steven. "Language Facilities in the Brussels Periphery". KULeuven—Leuvens Universitair Dienstencentrum voor Informatica en Telematica. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 October 2009. Retrieved 21 June 2007.Brussels is a kind of enclave within Flanders—it has no direct link with Wallonia.

- ^ Haß, Torsten (17 February 2003). Rezension zu (Review of) Cook, Bernard: Belgium. A History (in German). FH-Zeitung (journal of the Fachhochschule). ISBN 978-0-8204-5824-3. Archived from the original on 9 June 2007. Retrieved 24 May 2007.

die Bezeichnung Belgiens als "the cockpit of Europe" (James Howell, 1640), die damals noch auf eine kriegerische Hahnenkampf-Arena hindeutete

—The book reviewer, Haß, attributes the expression in English to James Howell in 1640. Howell's original phrase "the cockpit of Christendom" became modified afterwards, as shown by:

*Carmont, John. "The Hydra No.1 New Series (November 1917)—Arras And Captain Satan". War Poets Collection. Napier University's Business School. Archived from the original on 11 May 2008. Retrieved 24 May 2007.—and as such coined for Belgium:

*Wood, James (1907). "Nuttall Encyclopaedia of General Knowledge—Cockpit of Europe". Archived from the original on 9 August 2011. Retrieved 24 May 2007.Cockpit of Europe, Belgium, as the scene of so many battles between the Powers of Europe.

(See also The Nuttall Encyclopaedia) - ^ a b c d Fitzmaurice, John (1996). "New Order? International models of peace and reconciliation—Diversity and civil society". Democratic Dialogue Northern Ireland's first think tank, Belfast, Northern Ireland, UK. Archived from the original on 13 May 2011. Retrieved 12 August 2007.

- ^ "Belgium country profile". EUbusiness, Richmond, UK. 27 August 2006. Archived from the original on 7 October 2009. Retrieved 12 August 2007.

- ^ Karl, Farah; Stoneking, James (1999). "Chapter 27. The Age of Imperialism (Section 2. The Partition of Africa)" (PDF). World History II. Appomattox Regional Governor's School (History Department), Petersburg, Virginia, US. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 September 2007. Retrieved 16 August 2007.

- ^ Gerdziunas, Benas (17 October 2017). "Belgium's genocidal colonial legacy haunts the country's future". The Independent. Archived from the original on 25 July 2021. Retrieved 22 June 2021.

- ^ Braeckman, Colette (1 June 2021). "Belgium's role in Rwandan genocide". Le Monde Diplomatique. Archived from the original on 20 January 2022. Retrieved 20 January 2022.

- ^ Buoyant Brussels. "Bilingual island in Flanders". UCL. Archived from the original on 24 May 2016. Retrieved 5 June 2016.